Cognitive Model

David Hume famously posited that “you can’t get an ought from an is.” This statement draws a distinction between facts and values. Facts are how the world “is” and are grounded in concrete, physical reality. Values are about how the world “should be” and are grounded in more spiritual ideals. Focusing on facts versus focusing on values are two fundamentally different ways that you can construe reality, or the world. Under the facts framing, which I call the Science Lens, the world is a place of things. Under the values framing, which I call the Story Lens, the world is a forum for action.

The Science Lens describes the physical world. It is obsessively objective. Its fundamental elements are atoms and space and everything builds from there.* Right now my fingers are hitting keys which are making letters appear on a screen. The light from the screen is striking the rods and cones of my retina where it is converted to an electric signal that is relayed to the brain via the optic nerve. Blah, blah, blah. Richard Dawkins would be the spokesperson for the Science Lens movement, if such a thing were to exist.

The Story Lens, by contrast — or by complement — doesn’t describe the physical world. It describes the world of being.** The Story Lens is subjective. Its fundamental components are desires (aka goals) and actions. Or, for the mathematically minded among you, states and operators. These are the atoms and space of the Story Lens from which everything builds. Whereas the Science Lens concerns itself with nouns, the Story Lens rightly sees that the action is in the verbs.

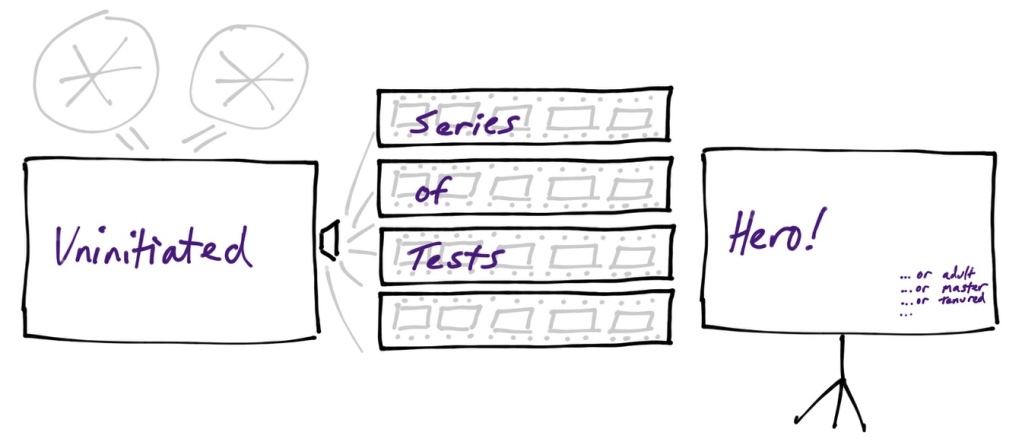

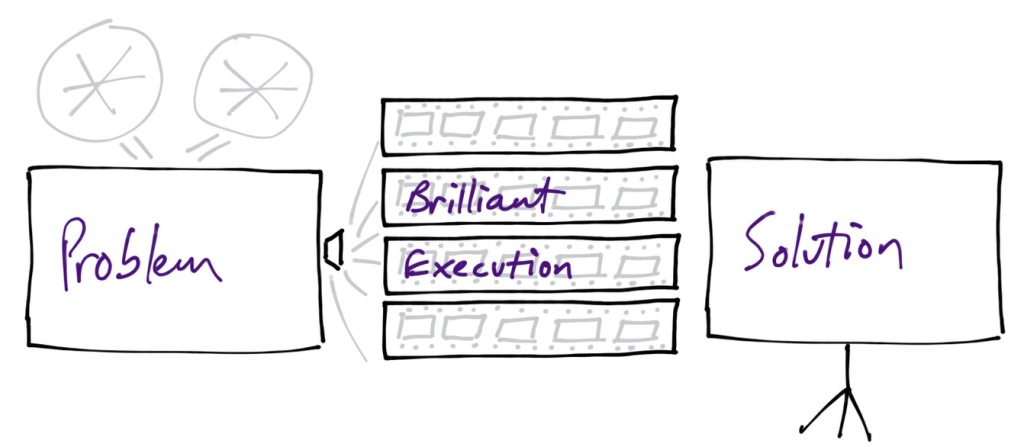

Below is what I label The Story Projection to frame the fundamental components of the Story Lens. At its essence, a story is about transformation. A person begins in an initial state. There is always something undesirable about one’s present condition. We’re always aiming up. It is this dissatisfaction that motivates the individual (perhaps the hero of the story) to pursue transformation. Stated differently, the unmet desire can be thought of as the problem that needs to be solved. The future, goal state, is the target. It is the solution state. The ideal that the story is aiming for. A sequence of actions is what propels our hero to a higher state of being. As they say in Hollywood: Lights… Camera… Action!

👆This is the Story Projection expressed at its most fundamental level for individuals.

👆For technical geeks. These terms span numerous scientific disciplines.

Application

So far I’ve defined The Story Projection as a cognitive model to frame human motivation and behavior. Now let’s apply it with some concrete examples.

Let’s start with Harry Potter. At the beginning, he is famous despite the fact that he hasn’t done anything. He lives under a staircase with muggles. But following a sequence of transformative magical adventures, he becomes the acclaimed wizard he was destined to be:

Harry Potter represents a more general story structure, codified at least as early as Ancient Greece. More recently popularized by Joseph Campbell:

The Hero’s Journey is about rising from a fallen state to a higher state, like the proverbial phoenix that rises from the ashes. This journey can span everything from a moment, to a day, to a lifetime, to a generation, and so forth. As you see below, one level of analysis is a single day in the life:

Zoomed out in time and space, and another level of analysis is an entire lifetime:

A child who becomes an adult. A technician who develops expertise and receives accreditation. A martial artist who reaches the next belt. A professor who achieves tenure. These are all manifestations of the same meta-journey or passage.

Finally, since I’m posting this on LinkedIn, I’d be remiss to exclude business examples. Generally stated, all business problem solving, goal-setting, and implementation is about acting out stories:

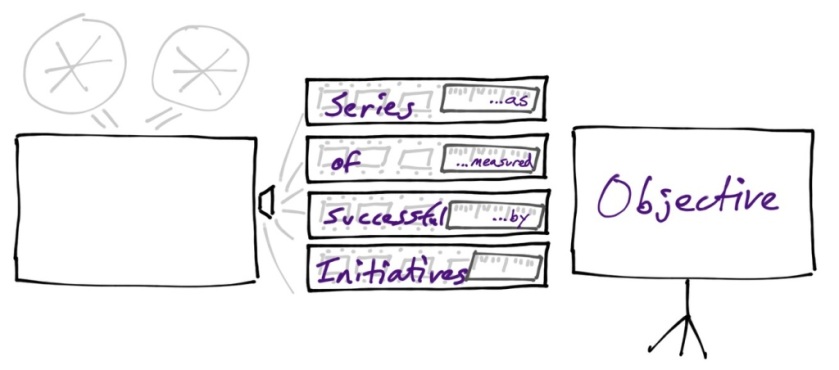

In Silicon Valley, OKRs (Objectives and Key Results) are all the rage. The Objective is the Goal State and the Key Results are the metrics that reflect successful execution of the goal. The phrasing of the Key Results starts with “as measured by” and provides evidence that the Objective has been met. While these results are outcomes instead of activities, any given outcome requires activity to achieve it. So a collection of Key Results are the consequence of a series of successful initiatives, or collections of activities.

The Story Projection is a very powerful complement to the OKR process. It provides a visualization that intuitively displays causality. Further, as I’ll explore in my next piece, the power of the frame really comes to life when it is chunked up or down to higher or lower levels of analysis. It shows the broader and narrower contexts to which the story in question belongs. For something like an OKR, it connects organizational goals up, down, and across hierarchies to demonstrate alignment of vision (or lack thereof…)

That’s it for now. Coming soon as a follow-up to this will be an article on The Story Projection across levels of abstraction.

* For example, you might start with quarks, build up to atoms, then molecules, cells, tissues, organs, organ systems, organisms, families, communities, cities, states, countries, planets, solar systems, universes, multiverses.

** Whereas the Science Lens is concerned with physical matter, the Story Lens is concerned with what is the matter.